Tranforming the preservation of digital art

On the 22nd and 23rd of March LIMA hosted Transformation Digital Art Symposium to discuss the ins and outs of media art preservation. Within the last couple of years, LIMA has established itself as a platform of international experts who specialise in exploring innovative approaches to media art conservation. As part of their ongoing Art Host project, the organisers invited artists, researchers and representatives from various institutions to address the burning questions – who should care for digital art and how could complex digital artworks be looked after in institutional settings?

A common thread running through the conference was the need for innovative institutional practices that would be able to support the rapidly changing digital art. In response to the challenges ignited by the new media art, speakers argued for digital preservation that needs to be:

Alive & Dynamic

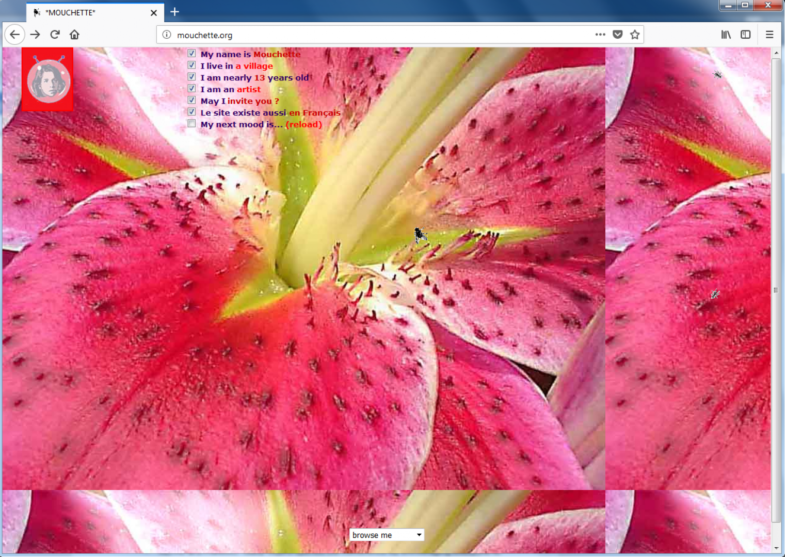

Director of LIMA Gaby Wijers opened the conference by encouraging everyone to embrace the uncertainty that comes with the digital art. The perspective of static historical objects that has been leading institutional practices is not capable of dealing with the liveliness of digital objects. For exhibition purposes, institutions can preserve timestamped copies of artworks such as Martine Neddam’s Mouchette.org by creating their offline version with reduced interactive behaviours. But to keep the actual artwork alive and working within the changing technological landscape, future alterations might be necessary. Of course, the very notion of alterations immediately raises red flags in any conservators mind since changes imply corruption of authenticity and originality. But as researcher Serena Cangiano rightly suggested, the value of the work does not lie in the dead fetishised object but rather in the living artwork.

Forward-Looking

Artist Constant Dullaart encouraged creators and conservators to explore ways to work around things that could potentially endanger future access to an artwork. Among other things, he suggested using contracts between institutions and artists that would clearly communicate what needs to be maintained to keep the work alive. Besides that, there is a need to identify things that cannot be preserved for the future, at least not in a traditional sense, and experiment with alternative conservation methods. A great example of this was documentation videos created by artists Geert Mul which demonstrated how even the temporal and interactive behaviours of his installations could be future-proofed.

Collaborative

As much as conservators would like that, not many artists start considering preservation from day one, if they consider it at all (and it is another question entirely whether it is their responsibility to do so). To bridge this gap between the needs of an institution and the artist, Rachel Somers Miles presented Artwork Documentation Tool which empowers artists to take ownership and document conceptual and technical aspects of their work that are necessary for future preservation. The use of such open-ended scripts is a great way to start a conversation between the two parties and make digital preservation scalable while avoiding the reductive one-size-fits-all approach.

It is clear that digital artworks demand a lively preservation approach, one that lives alongside the living artworks. Placing such objects in glassed museum cases is not a viable option. It is refreshing to see that institutions are coming up with innovative preservation approaches and embracing the complexity and interactivity of digital artworks not as their vulnerability but as their strength.